I am very attached to the courses I teach. I have toiled, sweated, and shed numerous tears building what I hope to be engaging lessons, organized units, and mesmerizing learning opportunities for each of the courses I teach. I, like so many of my colleagues sometimes feel that the courses I teach are my courses, my babies, my labours of love. I have caught myself saying and heard my colleagues say, “In my class,” and “the way I have designed my course.” If educators bring courses to fruition in their unique style that makes the courses theirs, right?

Nope. Full stop.

Just because educators have been commissioned to teach courses doesn’t make them theirs. There is no claim to them. But this mindset sure does explain a lot. It illuminates the traditional, colonial, teacher-centered view of courses and the assessment practices that accompany them. In a climate encouraging indigenous ways of knowing and learning and modern student-centered learning and assessment, why are educators so hinged to their courses, taking every missed day and task not handed in so personally?

Consider this. When you think about how teachers plan a course, where do you think they start? Do they grab a textbook and start at chapter one? Do they have a binder of units and follow it in order? Over social media, I have been asked if I have any good resources for a short story unit or what novels they should have their students read? When I was in teacher education, my practicum supervisors led with unit or task-specific focused course outlines. In English courses, it was and seems to be common knowledge that every teacher teaches short stories, poetry, one or two novels, a play, short story writing, and an essay. In Social Studies (Social Studies 8 in this example) begin with the Middle Ages, and then move on to the Renaissance, Reformation, perhaps including the Arab World, Japan, or China, and end with Early Canada. These practices are not wrong. There is a place, of course, for both the units and lessons. I’m talking about where educators begin their thinking and planning. My point is many teachers begin their thinking about courses with the units, lessons and tasks. As a result, grade books are designed with units, lessons and tasks as the focus. So, what’s the problem?

Grade books that reflect units, lessons and tasks have categories. In English courses, for example, there may be Assignments, Homework, Tests/Quizzes, Writing, Speaking and a Final Exam category. For Social Studies, there may be Assignments, Homework, Unit Projects, Tests/Quizzes, and a Final Project or Exam category. Each category is weighted and add up to 100%. All the categories combine to form a sort of grade soup, a hodgepodge and average of all tasks, each new task’s mark fluctuating the glaring overall percentage at the top. Mathematically, if the overall grade is low or in the middle, a high score on a new tasks shifts the overall grade up. How much it goes up depends on the category and how many points the task has been given along with how many points there are in total. A zero or missing task, depending on the weight and category, shifts the overall grade down. As soon a missing task is completed, even poorly, the overall grade goes up. This occurs because each task and its mark are a fraction of each category. Using this metric, the only way for a student’s grade to be 100% is for them to complete every task and receive 100% on every task.

Now, if grades should reflect what a student has learned, what they know and can do, missing tasks incorrectly impact the overall grade because no learning has been shown. It’s just missing. What does this do to the headspace of students when they are absent and miss several tasks over several days? They become anxious. The consequence of a plummeting overall grade is burdensome. Suddenly, there is pressure to complete the task rather than learn the material for the long term. Multiply that by four or more courses and students will inevitable, compliantly complete the necessary tasks, but the oomph put into the tasks will certainly be low. They are in, in the words of Larry the Cable Guy, Get er done mode. The mark is going down and handing in an assignment will at least slow down the momentum. It’s no wonder that students purposefully make decisions to sacrifice tasks to the education gods because the overall grade okay by them or their caregiver. The relationship to the task is weak but the relationship to the consequence is high. The grade machine and its malicious algorithm is to blame.

Learning material over the long term requires cognitive investment. In the Mind/Shift article, “How To Ensure Students Are Actively Engaged and Not Just Compliant” by Katrina Schwartz, John Almarode, an associate professor at James Madison University says, “Everything we know about the neuroscience of learning is that emotion drives cognition, [and if a student] isn’t actively making meaning out of the information, then active engagement still hasn’t been reached.” He goes on to say there needs to be behavioral, emotional and cognitive engagement at play together for there to be true engagement.

And what about how individual teachers determine their categories and weighting? One teacher gives 10% completion credit for homework while another teacher does not. One teacher gives half credit for corrections while another does not. One teacher insists on being on time for a quiz or students receive a zero with no opportunity to complete it. One teacher weighs projects more heavily than writing assignments. One teacher gives an extra 5% for participating in a workshop at the end of the course. Another teacher gives students the chance to teach a unit to themselves and earn bonus marks. The varying degrees of constructing grade books doesn’t embody our autonomy over our assessment practices, it illuminates the inequity between teachers. There is no consistency. There is no reliability between courses when teachers who teach the same course generate grades using different methods and expectations. Here’s another truth. Students choose teachers based on how they grade and who will present the easiest route to passing. I’ve heard them say it. Who pays for it the most? Students.

This brings me to the problem with course credit opportunities when grades are teacher-centered. Course credit opportunities usually apply to students who have failed a course but are close enough that they can earn a passing grade through modules. In British Columbia, the folks who need to do modules are usually sitting between 40-49%. Now, I’ve seen instances in which the student’s classroom teacher is directly involved in this module process, determining the most important units’ students missed in order to earn credit. I appreciate this method because not only could it be an opportunity for the teacher to be involved with the student’s journey to earn credit, but hypothetically speaking, the relationship between the student and teacher could be restored if it has been fractured during the course. Students feel hopeful when they are given another chance. Problems occur when teachers expect students to complete too many assignments based on the mindset that if all students had to do them, this student should too. This isn’t giving students a chance to pass, it’s demanding compliance.

Further problems arise when a teacher is assigned the responsibility of assigning and monitoring module. It is up to them to decide how best to get a student to 50%. This isn’t a criticism of that teacher’s ability as they have been unfortunately tasked with an unwieldly objective. Instead of filling in the actual learning gaps, because all this teacher has to work with is a percentage, they do their best to top up the student with tasks until the grade machine pings at 50%. The student might not need to do a graphing unit to pass Math 9, but let’s get them to do it so they can earn the points. Their comprehension might be adequate, but let’s have them read three stories and do some comprehension questions for the necessary points. Eventually, when the original teacher notices that their student has been given course credit without any communication as to how they achieved that credit, I can sympathize with their frustration. I can further sympathize with the subsequent grade level teacher when they quickly determine that many of the gaps that needed to be filled to be prepared for the course has not been filled. It’s a mess.

Problems like this are a direct result of a teacher-centered approach to assessment. Grades go up when students attend and hand tasks in and go down when they are absent and don’t hand tasks in. How is the overall grade measuring learning if grades are determined by all the stuff students must do? By that rule, students do all the stuff teachers create for them to do at 50% competence, they get 50%, or if they do half the stuff teachers create perfectly, they also get 50%.

It makes my head hurt.

Let us go back to the beginning of this post to see if we can navigate our way out of the grade soup mess. I’ve already stated that the courses I teach are not my courses; the courses any teacher teaches are not their courses. Courses, managed by the Ministry of Education, include principles teachers are supposed to follow to guide their instruction.

What if teachers started there instead of with the typical units, lessons, and tasks? Expectations for each course is presented through their curricular competencies and content. At the top of each standard, there are the phrases, Students are expected to know the following and Students are expected to be able to do the following. If teachers begin here, understand and unpack these standards, and then co-construct criteria for each standard with their departmental colleagues, they will effectively be on the same page about what students are expected to know and do. Take this a step further and when teachers track evidence of learning (from those typical units, lessons, and task) using only the criteria for the standards, they can decide what evidence best represents a level of proficiency. At reporting time, if they use professional judgment to evaluate each standard and a logic rule (or something akin) to determine overall grades or proficiency scale levels, what they will have is a grade determined solely by standards and representative of….learning! In my February 12, 2023 post, “The Love Language of Professional Judgment,” I state, “Professional judgment becomes a love language when educators match performance to a level of quality…[If] educators in the same department can agree on criteria, then students know that no matter whose class they are in, the criteria will be the same. The learning opportunities and delivery will be unique to each educator, but how students are assessed will be consistent. When educators have unique assessment platforms with varying categories and overall grades determined by electronic grade books and confusing algorithms, it confuses students, breeds resentment amongst educators … and entices students to chase percentages rather than learning because the overall percentage is the only part of the assessment process consistent among all educators.”

This is not how I was taught to assess in teacher ed and it will be new to many teachers. But it’s not actually a new idea. It’s not a unique idea that will eventually die out neither. Standards based grading has been around for a long time. It’s just been ignored because the system was designed originally for efficiency. Rack up the points, punch in the grade. Done. We know better now. While we still might need grades especially when it comes to reporting grades to post-secondary institutions, what they mean can be more compassionate, thoughtful, and inclusive than the hodgepodge grade soup approach. It is not ironic, folks, that the words, Learning Standards are displayed on our curriculum. Maybe if there are standards, we should be doing…standards-based grading.

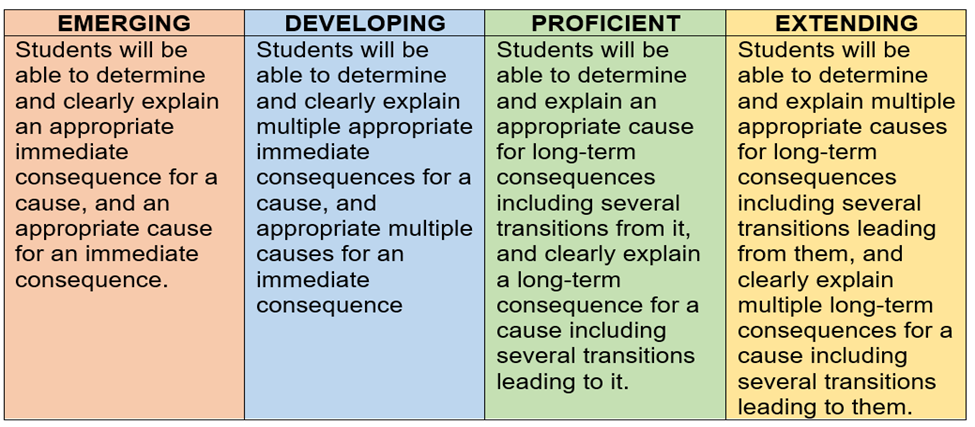

So then, what is passing in standards-based grading? Passing should be granted when a student supplies sufficient evidence of learning of the curricular competencies and content standards at an Emerging level. (In British Columbia, there are four levels of proficiency: Emerging Developing, Proficient, and Extending). As mentioned before, it will be more effective if groups of educators co-construct what this means. When students have not supplied evidence of learning at an Emerging level, it should be noted as Insufficient Evidence. If departments of teachers can determine what each level quality looks like then it will not matter what class a student is in, the requirement will be consistent.

Communicating learning will then not be about what stuff students did, it will be about to what level of proficiency the student meets the standard. When students need course credit, it won’t be what each student owes that teacher or much stuff to top them up to get to 50%, it will be what evidence of learning at an Emerging level does a student need to show for that standard?

In the last week of my Humanities courses, students are given a progress report with an evaluation of each each standard. Prior to this, I created separate learning opportunities for each standard. Students determine which standards they want to level up in if they are Emerging or higher, and students who have Insufficient Evidence must do them. Before they provide this evidence, I do some reteaching. Students examine former learning opportunities and the feedback that accompanied them. Some didn’t level up and had to try again a few times. Others made it on the first attempt and then did it again so I could be certain they were at that level of proficiency. Simply completing these learning opportunities does not automatically improve their grade. They must meet the level of proficiency that is the goal. If a student ultimately fails my course because there is insufficient evidence in two or more standards, I communicate that with their caregivers and whomever oversees the modules, and we figure out next steps. To be fair, in the past few years, I’ve never had to go so far as to connect with that teacher because the week students had to level up was sufficient.

I generated the criteria for these standards on my own. While I oddly take pleasure in building proficiency scales, I worry that the criteria I have chosen isn’t consistent with what my colleagues would deem as sufficient. As much as I pride myself on carefully developing criteria, I would rather co-construct it with my colleagues and work on it as a team. Not only with this build equity among us, but it will model collaboration for our students.

There are other advantages to shifting to standards-based grading and building criteria with colleagues.

When Emerging level criteria is developed by departments, teachers can then scaffold instruction and add in windows leading up to Emerging if one or more students are not able to hit Emerging. On the Tom Schimmer Podcast, inclusion expert, Dr. Shelley Moore suggests while Emerging is where students at grade level should be, but that doesn’t mean that is where we have to start with our learners. So, it is good to have the four levels of proficiency criteria, but then, we should add in what Dr. Moore calls, “windows” or access points before Emerging if students are not ready for Emerging. She goes on to say that students need to feel success before moving forward, and by creating these steppingstones, educators can celebrate student’s success and students will feel successful. This is planning for the range rather than planning for the average.

Furthermore, students want clarity around how they are being assessed and the transparency of criteria supports this aspiration. In the article, “Student and Teacher Motivation, in Charts,” by Arianna Prothero, students were asked, what their teachers could do to help them feel more motivated to do their best at school. What should catch your eye in the chart below is 35% want the chance to redo assignments and 29% want more feedback so they know how to improve before getting their grades. I realize that this is a representative sample and not my students, but it’s interesting. In a standards-based classroom, students receive multiple opportunities to reach their proficiency goal and earlier, weaker scores are thrown out when more recent evidence shows progress. So, the criteria in the proficiency scale can serve as feedback because students clearly know what the expectations are.

In British Columbia, the new reporting order is an opportunity to let go of teacher-centered practices and embrace more student-centered ones. It’s ego really. When teachers feel they have invested so much of their energy into units, lessons, and tasks, when students don’t live up to their expectations by doing all the stuff, they take it personally. It’s time to let that go. Standards-based grading serves our students better. What students don’t need is another report card that is another serving of grade soup.

#MyGrowthMindset

2 thoughts on “Stop making grade soup”