I’m aware of the hyperbole in the title. The world is a big place. The world is…THE WORLD.

When I started writing this piece, I considered toning it done to, I want to change learning, one proficiency sequence at a time. I contemplated, I want to change education, one proficiency sequence at a time. I kept going back to the words, change the world. I really do want to change the world.

I know that sounds nerdy and a tad overreaching, but I think that assessment is the key to change, definitely in education. I think learning and education are components of this vast world and I also think that the impact I make on students, positive and negative will have an impact on their future life, not just their current life and not just their school life. The social emotional impact of assessment and evaluation is real. They’ve told me so.

Students have told me that they feel unseen and unheard. Recently, when I introduced myself and my assessment pedagogy to a bunch of wide-eyed English students, I asked them a question, What do you expect from school? Many shared that they expect to feel safe, receive help with their learning, and have compassionate teachers. Then I asked them, What does school expect from you? The subsequent responses were a shot in the heart. What reverberated across the room like rapid machine gun fire, “Teachers expect too much, they don’t understand that we have lives after school, they don’t understand our workload, they don’t understand that we have other responsibilities, and they want us to treat their class as more important than other classes.”

Whoa. Chew on that for awhile.

“Sometimes I have hours of homework on top of soccer practice,” one student remarked, “and I don’t get to bed until 1 am. Then, sometimes, I sleep through my alarm clock. I just got hauled into the principal’s office for skipping period 1. I didn’t mean to skip. I was sick all last week and now I have a four overdue assignments. I’m still sick. But I have 52%. I’m almost failing. It’s never ending.”

That was just one of several stories shared in the room.

My heart fell. A lump formed in my throat. Their passionate discomfort was real and alive. At first, I didn’t really know what to say. I wanted to shout, “Hell yeah!” or “Amen, brothers and sisters!” but I quickly realized that wasn’t what they needed. What they needed, yes, was an ally, but they also needed the voice of calm. They needed a teacher who wouldn’t intimidate them and would appreciate their frustrations. They needed this class feel heard.

Enter empathetic teacher with an assessment mission they had never ever saw before in their lives! Pray for me.

“So how about,” I began with a little vibration in my voice, “we take grades out of the equation and just focus on the learning?”

Crickets.

“What if,” I continued, trying not to make direct eye contact with any of them, “the learning you do in this class is evidence of learning. I’ll provide the pathway to success, you put in the time and effort in class, and I’ll provide the feedback in real time. If you miss an assignment, we’ll decide, together, if you need to provide more evidence or if I have enough. We’ll use a five point scale and not worry about your overall grade until report card time.”

More crickets.

Then, just as I was about to fold in the towel and move on to something, anything else, a hand shot up. “So, we won’t get a zero for a missed assignment?”

“Nope.”

“And you won’t give out homework?” another student commented.

“Nope…with the exception of silent reading, no homework. You will be able to take your work home with you, if you want, but you won’t have to. I want great quality work instead of lots and lots of energy in that work. I want you to go home and be a kid.”

The students looked at each other with some confusion, but there was also some enthusiastic chatter amongst them as well.

In the following weeks, I had to dodge the expected, “what grade do I have?” and “is this for marks?” but incredibly, after a few whole class discussions about those said questions, many slowly became comfortable with my assessment practice.

I also put my money where my mouth is and followed through on my promises. I didn’t give out homework. Students knew exactly what was expected of them because I used proficiency sequences, a task-neutral pathway of learning directly connected to BC curricular competency standards and aligned to my district’s five-point proficiency scale.

Instead of giving students a task-specific rubric, I focus on the curricular competency standard and the various learning opportunities become evidence of learning for that standard. With this mindset, multiple evidence of learning supports the overall evaluation of the curricular competency standard. The best or most consistent evidence dictates the ultimate evaluation. There are no averages in my assessment world. And if a student misses one learning opportunity they don’t necessarily have to make it up. In a discussion with the student, we determine if the evidence is needed, if a different piece of evidence is required, and what our next steps are.

Let me give you an example.

Below is the proficiency sequence for, Respond to text in personal, creative, and critical ways. Prior to having students work through the sequence on their own, they practiced each level in class. This is ungraded practice in order to grow comfortable with the sequence’s language. Each level in the sequence is more complex, but by practicing each level without penalty, students feel freer to take risks with the criteria within each level, have the opportunity to conquer each level, and then can use their own agency over how far they want to want to go on the sequence once they are given the opportunity to do it on their own.

For this sequence, after we practiced each level, students watched a documentary and we co-constructed expectations for a poster assignment. We agreed that five pieces of information in response to the documentary would be Applying/Proficient (Could do) and more that five would be Extending (Try to do). Each detail needed a picture, but the picture need not be perfection. We all agreed that the response would be assessed on the quality of the response, not the quality of the art. Co-constructing some of the criteria is powerful.

Now, one student was absent for the documentary, so we sat down to decide what other text could be used as a replacement. This is a very common practice in my classroom. You weren’t here; let’s see what curricular competency we worked on and how you can provide evidence of learning. This student decided to use a Ted Talk, a less time consuming and more accessible text. Another student requested to watch a different documentary on Netflix. And another student with autism, who watched the film but felt anxious staring at the screen, requested an article about the film to use as the text. All replacements were valid and varied.

On each of the above students’ report card progress reports, which came out only days after the assignment was due, they received an insufficient evidence until evidence of learning was provided. After the evidence was provided, a new progress report was generated. No zeroes, no reduced grades/percentages. Just a remark that the learning hasn’t been provided…yet.

Yet is a powerful and sympathetic response. Too often overall grades and percentages invoke ego, cheating, and surrender.

Why use a proficiency sequence? Why not use a rubric?

A proficiency sequence is directly connected to the curricular competency standard language. The assessment my students receive are standards-based assessments. Ultimately, if I have decided to focus on five or six power standards, there will only be five or six evaluations. Each learning opportunity I create for or with students are directly connected to one standard (the odd opportunity is connected to more than one, but I really appreciate making the learning intentional to one standard, so students really understand what the standard is asking of them.)

Rubrics, as I have created and used in the past, are created for specific learning opportunities or tasks and often danced around the curricular competencies but didn’t flow from learning opportunity to learning opportunity. In other words, I wouldn’t use the same rubric for all pieces of writing, for example. I had a rubric for short story writing, another for paragraphs, and another for essays. That was because in addition to only touching on the curricular competency standards, there were also extraneous, unrelated criteria set in stone. When each learning opportunity was assessed, the grade went into the grade book and the learning was over. There was no continuity from learning opportunity to learning opportunity. I always allowed rewrites and retakes, but that just felt like haphazard corrections for a task.

Generating proficiency sequence criteria immerses me in the curricular competency standards and their intention. I have to do a deep dive into the verb and the language surrounding it. In doing so, the criteria feels incredibly powerful and specific to the curricular competency standard. Then, when each learning opportunity is viewed through the lens of that criteria, there is no way I can include extraneous criteria because I’m assessing that standard, not the task.

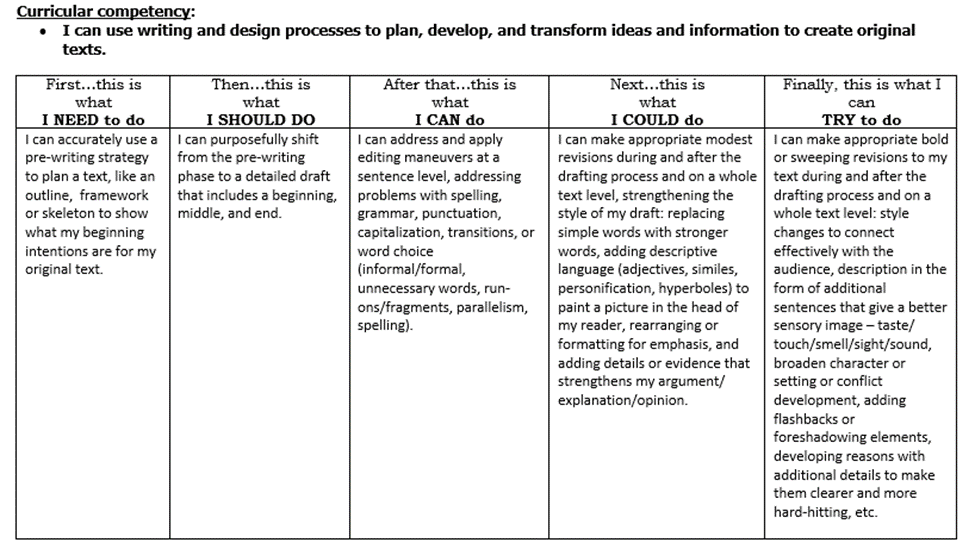

Here’s an example using my favourite proficiency sequence for writing. When I generated this criteria, I noticed that it really focuses on the moves writers make. With the moves of editing and revising as the focus, I must purposefully avoid including things like paragraph size number of sentences, for example, in my assessment.

For the above sequence, imagine how powerful it would be to tell a student that the focus is on your writing process? How many student do you know who think they are stupid or feel unsuccessful because they have dyslexia, dysgraphia, or struggle with output. Consider now the significance of the criteria above. This sequences gives students permission to try, fail, get messy, wrestle with language, and show improvement…individual improvement in all their writing pieces. This sequence not only honours the learner, but it is also more equitable.

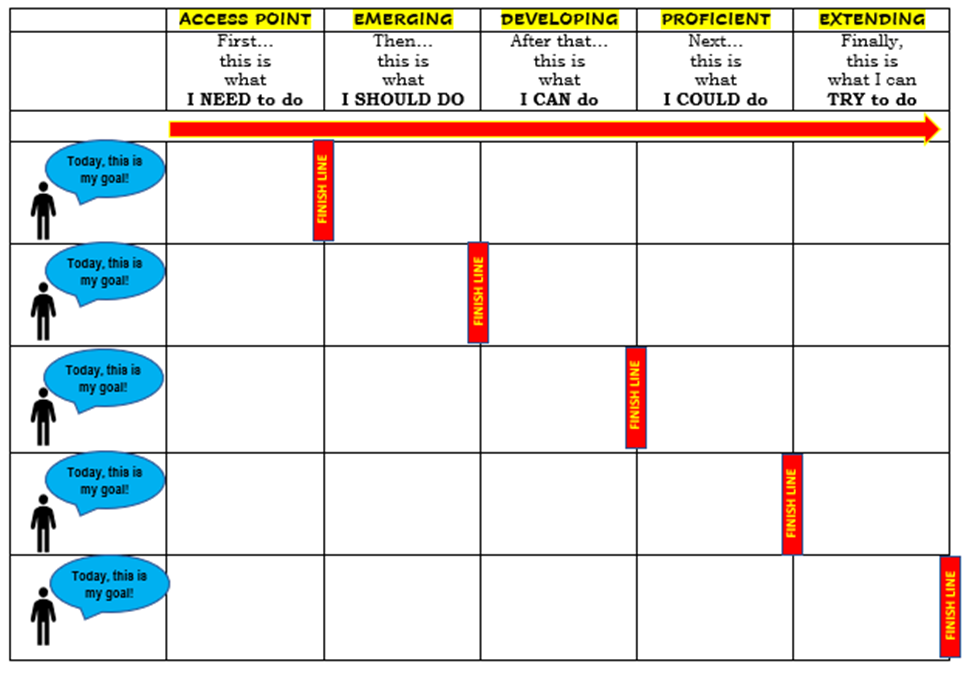

Proficiency sequences are also different than rubrics in that students move through the sequence from the beginning, as far they can. All students begin at Need to do and then carry on to Should do, Can do, Could do, and Try to do. The language one uses when building sequences is irrelevant; the criterion within each level is what is meaningful!

Sequences also provide different finish lines for each student. What a profound way to view each student’s individual learning progress for a curricular competency standard! Viewing the proficiency sequence as a learning journey supports the shift away from an ego invoking grade culture. Sure, the sequence aligns with proficiency scale levels, which are in fact grades, but because there is the promise of several laps of the standard, learning is not reduced to a finite learning opportunity. One student is Emerging now, while another is Developing, but now both have goals to achieve the next two or even three levels on the proficiency sequence. Both may, in fact, be Developing by the next learning opportunity.

The birth of the proficiency sequence

I started making proficiency sequences when I was teaching Drama 10. While I understand and still buy into the purpose of Proficient level criteria within a single point rubric, the mindset being that if that criteria are the only goal, students will achieve it, for some students, Proficiency was out of reach, and they needed timely goals that were achievable for them.

When I included criteria for Emerging to Extending within the single point rubric, it was more purposeful but cumbersome and awkward. But when I tilted it 90 degrees to the left and labelled what criteria went with what level on the proficiency scale, students could see where they were and what their next goals are.

However, these sequences were still task-specific, so then I set out to do the same thing but for individual curricular competency standards. Simply put, I listed all the criteria I wanted to see for the standard, and then ranked and sorted that criteria from Emerging to Extending. I focused on the verb, used Bloom’s taxonomy to keep the criteria consistent, withheld content from the process so that the sequences could be used with various topics/units, and built in both what was expected and how well students needed to show in their learning. Voila…the birth of the proficiency sequence!

What proficiency sequences aren’t

I think it’s important before I continue to clarify what proficiency sequences are not.

Much of the chatter on social media explains the difference between proficiency scales and learning progressions. Proficiency sequences align with proficiency scales in that as students move through the sequence, where they arrive and if they meet all the criteria along the way, they will be assessed at that proficiency scale level. For example, student A moves from Need to do…to Should do…to Can do. They will be assessed at Developing.

Proficiency sequences focus on the verb in the curricular competency standard. Progressions tend to show the steps leading to the verb. In other words, if a standard asks the student to analyze, the progression might follow a taxonomy of learning that begins with knowledge, then understanding, then analysis, with the opportunity to Bloom up to say synthesis after that.

Progressions do not align with a proficiency scale. A progression for writing might look like, learn to write a thesis paragraph àwrite body paragraphs à add in transitions, and àwrite a conclusion. If what I just mentioned was treated as a sequence, then it would be suggested that the more paragraphs a student has, the higher the level on the proficiency scale, and that just doesn’t make sense. Progressions tend to be moves and motions and don’t take into consideration complexity and the verb in the standard.

Let’s try another example. When I first jumped into the current BC curriculum, I did so with gusto because Tom Schimmer led the way with a series of videos and a lovely explanation about how to approach the BC four-point scale and what four levels of complexity on the scale might look like. He used a pancake analogy that I still refer to, today.

Schimmer explains that if the standard is “making pancakes,” than assessing pancakes means one needs to show what four levels of pancakes look like. There would be Emerging pancakes, Developing pancakes, Proficient pancakes, and Extending pancakes. A learning progression would be a series of steps beginning with knowing dry ingredients and wet ingredients like milk, eggs, sugar, etc., combining the wet ingredients and dry ingredients separately, combining the wet with the dry, and finally making pancakes. He cautions teachers that knowing flour, milk, and eggs is not Emerging, combining wet ingredients is not Developing, combining the wet ingredients and dry ingredients is not Proficient, and finally making the pancakes is not Extending. Are all these steps important? Absolutely. Unpacked like this, though, is not analogous to the proficiency scale.

So instead, there needs to be criteria for four made pancakes. If I were to manufacture a proficiency scale for four levels of pancakes, it might look something like this:

Notice how all levels use the same verb, make. A polished proficiency scale OR sequence needs to maintain the verb. That’s where a taxonomy like Bloom’s is paramount in importance when building these suckers.

Okay, so the above is a proficiency scale. It’s not a proficiency sequence. To create a proficiency scale, what I might do is consider the techniques needed in the making of pancakes that result I the above expectations, while maintaining the verb in question. When I create this criteria it will be strength-based, like a hill they need to conquer on a run, and each level will need the one before in order to advance. The language needs to be easily followable, a pathway.

In all levels, the student won’t know if they have reached that level until they make the pancake so it isn’t a progression. Additionally, each level is not simply the checking off of a box as in a learning progression. The techniques get more sophisticated as the student moves through the sequence. Learning to manipulate and adjust the temperature at Try to do takes more finesse than flipping (at least in my head it does…and remember that I am an English/Drama teacher, not a Foods teacher).

Building the sequence is really about visualizing the standard in action. Now you might disagree with the order of operations in my sequence for pancakes, and sometimes when a proficiency sequence is in action, I discover that I screwed up the order. I think it’s important to make any rubric or scale or sequence and own it. I used to get really flustered about building the perfect proficiency sequence for each competency. Then, ironically, I listened to a recent Tom Schimmer podcast about rubric making and realized that assessment is a fluctuating learning experience; it’s better to own it and make modifications for next time. So, now, if I do realize that the order might be incorrect for some students, I tell them to leap over and then double back. The result will still be the same, assessment-wise.

Now the real beauty is in how unpacking the standard and developing the process gives teachers the chance to teach each level. Take your time. Maybe even have the students explain why each level is the way it is. Delve into the necessary content. Explain that if the batter runs to the edges the moment it is poured, as if it is running away on them, there’s something wrong with the batter and it’s time to start over. Let student practice flipping techniques with a teacher-made batter so they get the hang of the wrist action required in the Can do level of the sequence. Modelling and ungraded practice is key.

Once they’ve made their pancakes, students can use the sequence to self-assess. Where did they struggle, what did they conquer, and what are their goals for next time? If the teacher gives plenty of time to try, fail, get messy, wrestle with it, and show improvement (yup, I used those same words earlier), you’ll find that many students get all the way to Proficient (Could do). And if they don’t, add on another day! Let them try again! Another day is good for all students regardless of the level they reached. The kid who is already Proficient can still practice and the student who isn’t gets another shot. Don’t shut the door on learning due to time. Personally, I’d rather teach fewer standards and see more proficiency that teach numerous standards and see a hodgepodge of levels because time and moving on to the next unit is more important than the learning. Boom.

Now, making pancakes is not really a curricular competency standard…duh. Plus I understand that it reads more like a task. I hope it clarifies the process I use when building a proficiency sequence. In the actual BC curriculum, each standard is very vague, so I recommend simplifying the language before developing a sequence. If you have looked at any of my proficiency sequences (two are included in this post), you’ll notice that they can’t be found in the BC curriculum because I reworded them while still honouring the verb in the original. You’ll also notice that I haven’t developed separate sequences for different grade levels. Many of the curricular competency standards reoccur from grade level to grade level. The natural, knee-jerk reaction would be to define specific grade-level criteria then, right? I thought so too, initially, until I heard Dr. Dustin Louie speak.

Dr. Louie is a First Nations scholar from Nee Tahi Buhn and Nadleh Whut’en of the Carrier Nation of central British Columbia. He is an assistant professor at the University of Calgary’s School of education, and has taught courses related to indigenous education, social justice, and educational philosophy. In Dr. Louie’s presentation, he spoke about how traditional indigenous learning is cyclical, meaning that children need multiple opportunities to develop the same skill over time. This made sense to me because I’ve never fully understood how learning should be this finite process confined to five months in a semester or ten months in a year. That mindset led to the “learning gaps” thinking that we’ve heard so much about as a supposed consequence of online learning and students not coming to school because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

True, and especially in high school, there is a pressure to learn more and more content, and a desire to increase the level of sophistication of processes and skills from year to year, but the essence of these processes which are the curricular competency standards can and should stay the same. I might want my English 9’s to write an essay and use that as the learning opportunity for the writing standard, but if I have a student who needs to focus on paragraphing first, they can still use the writing proficiency sequence to develop that paragraph. It’s better to let go of the what and have the student work on the how and how well. Maybe one student will write three essays in a semester while another will only write one. So what? In both cases, there is evidence of learning. That evidence of learning can be used evaluatively for that standard. How coolly individualized is that?

In conclusion

So, I need to return to those students who I introduced proficiency sequences to and attempted to take the pressure of grades out of the learning process.

Many of those students, when they reflected on their learning at the end of the course, spoke very highly of the proficiency sequence method. They made great recommendations too, like, colour coding the sequences so they are more easily accessible, generate headings for each curricular competency so that it can be referred to as simply “the comprehension competency” or the “the writing competency” or “the discussion competency,” and they wanted to be involved more in the process of developing this criteria too as they did in the respond to text one. They asked for the opportunity to receive only the minimum criteria and then let them do the rest. All of this feedback has and still is incredibly powerful and thoughtful; I take feedback to heart.

In addition to the critical feedback, though, they also spoke about feeling heard and appreciated. They also felt sad and frustrated that their next year in the same subject might not yield a teacher who has the same mindset. It wasn’t really about the sequences, they told me, it was about the opportunity they received to be successful, that they didn’t feel like they couldn’t do it anymore or can’t be a writer or reader or learner. They appreciated the transparency of the sequence but felt that the sequences went far beyond the learning and focused on the learner.

Will proficiency sequences change the world? If they don’t change the world, will it change education or change learning? I’m actually not sure. It’s one of many ways teachers can approach standards-based grading and learning. It’s not the only way. Many of what, I feel, are their beautiful characteristics can be found in other assessment practices.

For me, it feels pretty good knowing that so far, teaching to and using proficiency sequences has been a positive evolving experience, and when implemented in a way that honours the learner and their journey, providing voice, choice, agency, and opportunity, I think that changes the learners’ world, so I’m all in!

#MyGrowthMindset

This post is EPIC. So appreciate your careful thought, the way you reach students, and the incredible MISSION behind your work. You are shaping the learning landscape in BC and yes – around the world. Keep going, Shannon!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Once again, another great read. I always enjoying hearing about your experiences and how you are continually learning and improving your assessment practices. I am eager to try building some proficiency sequences for my courses. I would love to hear more about how your students were involved in developing the criteria. I tried this with my Chemistry 11 classes this year, and it worked really well. It took some guidance but like always, they impressed me. My students had a much better understanding of the competencies and what each level on the proficiency looked like.

LikeLike